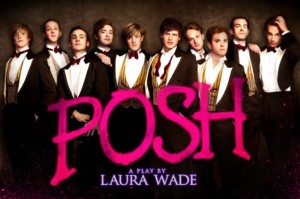

A Wednesday in early July found me down in London at a matinee of the West End revival of Laura Wade’s Posh (Duke of York’s Theatre). Coming out of Posh, I couldn’t help but overhear the post-performance chatter of a group of young (university-age) spectators close by me. They were puzzling over the play’s politics. A woman in their group had the final say: whatever these were, she concluded, they were put in for older audiences, while the show’s privileged-boys-behaving-badly comedy was there to entertain and please a younger crowd such as themselves. Such a view does, however, rather miss the political point of the play: the satirical bite of Wade’s drama locates in its class-attack on ‘posh’ boys. And I would like to point out that this feminist ‘oldie’ derived a good deal of audience pleasure from Wade’s darkly funny portrait of the private, all-male ‘members’, Oxford boys’ dining club.

Originally staged at the Royal Court Theatre in 2010 around the time of the General Election, Posh attracted a good deal of press interest because of the inferred connections between Wade’s fictional Riot Club and Oxford’s Bullingdon Club of which Conservatives David Cameron, Boris Johnson and George Osborne are reputed to have been members. The play was updated for its West End run: lines were added to make reference to the Conservatives as back in power, albeit in a Coalition government; the economic crisis in Greece gets an airing through the Greek, Oxford boy, Dimitri. Overall, there’s a zeitgeisty feel to this post-election revival of the play: the elite boys are back, behaving badly, while ordinary people suffer the consequences. Wade captures this beautifully as her ten ‘posh’ male diners secure a private room in the Bull’s Head Inn for their riotous behaviour – an evening of excess that climaxes in the trashing of the restaurant, with tragic consequences for the inn’s landlord. I admit I experienced a visceral pleasure in the trashing sequence, partly because it made me feel like I wanted to get up and smash a chandelier or two myself, and also because it was impossible not to feel an echo of the recent riots that took place not in private dining rooms, but in public spaces, out in the streets. And feeling this hits a political nerve: the privileged boys get away with their trashing, even while one of them is scapegoated for the night’s events; England’s disillusioned and disadvantaged street rioters did not, as we know, go unpunished by the powers that be.

Nor is this an isolated incident of posh-boys-behaving-badly, but rather Wade’s point is that this has gone on for centuries. Amid the riotous dinner there comes a haunting reminder of inherited privilege: in a rather odd flight into fantasy the ghost of the club’s eighteenth-century figurehead, Lord Riot (played by one of the boys) joins the table, chiding them for squabbling among themselves, and urging the reminder that they are ‘the brightest, the boldest, the best’, destined to ‘lead’. Far more effective than this lordly apparition, however, was a wonderfully performed ensemble momentearly on in the show in which six full-length portraits of old, aristocratic figures, hung side-by-side in two rows with three pictures apiece, were brought to life by the cast. Animating the portraits, today’s generation of Oxford boys step into or are ‘framed’ by past histories of privilege. And so, Wade’s drama contends, the inherited ‘right’ to riotous behaviour carries on from one generation to the next.

Decanting her comedy from this privileged Oxford set Wade heightens her class and gender critique. There are only two women in the cast: one is Rachel, the waitressing (but also university-educated) daughter of the inn’s landlord, the other is Charlie, an escort hired for the night by one of the boys. A second-wave feminist play might have drawn a different gender line, taking the woman’s part and refocusing on women as the verbally and physically harassed victims of the boys’ misogynist behaviour. But Wade’s women eschew the victim role and stand their ground. Charlie refuses to accede to the boys’ request that she service all of their group ‘members’, while Rachel shuns their attempts to make her the sex substitute for Charlie. There came a point, as the drunken boys gathered riotously around Rachel, when I felt the drama was on the knife-edge of a rape scene, though Wade cannily shifts the escalating violence away from Rachel, leaving the father as the hapless target of the boys’ drunken aggression.

The play ends where it began (back in a Gentleman’s Club in London), and with a concluding sense of a behind-the-scenes cover-up, with the smartest of the group, despite being the scapegoat for the evening’s events, seemingly set for a brilliant political career. It is a chilling conclusion – chilling because, unlike the young group of spectators who came out entertained but puzzled by the politics, I left the theatre feeling the cathartic release of having being able to laugh at the ‘posh’ boys, but also the discomforting recognition, prompted by the drama, that out in the real corridors of political power this is no laughing matter, no laughing matter at all.

Elaine

I loved this play! I was 17 last summer when I saw it and do not worry – the jokes were not wasted on me nor on my friends.

Your analysis of the ending is also spot on in my opinion

Thanks for the read

After reading your post, I am left with the belief that your knowledge of this subject is better than other blogs I have seen in the past. Cheers.